Caspar’s Cases #5 “Apraxia and the Imperfect patient”

Differential Diagnosis and the Damned – cases and complications

The ‘best laid Research Plans…’ [1]

As I mentioned previously[2] my research was on ‘apraxia’, an inability to effectively plan and learn patterns of movement, due to brain damage. I had been aware of the ramifications of brain damage since I was 10 years old. It was the unfortunate fate of a member of my extended family, which made a lasting impression on me. In 1961 My father’s identical twin brother’s family (with 2 boys and a girl) moved in with our family of three boys. The crowding wasn’t the problem. The arrival of the additional 4thcousin was. He had been born about that time with a diagnosis of ‘cerebral palsy’ (not the athetoid kind which Andrea Andersonhad). His mother (my Aunt) and the whole family were stressed out with worry and changes in life-style to accommodate this little bundle who couldn’t move or talk properly. Observing his slow process of learning to walk and not learning to talk, was not just pathetic, but also annoying and frustrating that there was little available from allied health workers, especially speech therapy and physiotherapy, and no psychological help for his mother and the family.

These observations influenced my pathway into Psychology. Despite my University Psychology Department not having much in the way of expertise in human movement and cognitive psychology, I pursued extra courses at a neighbouring University in my intent to understand the brain’s control of movement and the learning processes involved. So it was I prepared myself for higher-degree research into the Neuro-Psychology of human movement. But to get to be able to interact with and study patients with movement disorders, I would have to gain the trust of the hospital experts and show I could be useful in helping with various disabilities. My research was not embraced by the academic Psychologists, who saw movement studies as the poor cousin of cognitive psychology. So I asked the Chief Psychologist, Dr David Dennison, if he would introduce me to the Neurology Department and allow me to attend its staff seminars, especially the “Grand Rounds”.

Always the conservative professional, Dr Dennison said he’d think about it, as it depended on my performance and the way I interacted with the other professionals and the patients in the hospital. Time went by and he didn’t follow-up on my request. However, he did keep referring me various cases for assessments and standard Psych evaluations.

So I bided my time gathering my research literature review, sitting in classes of the various academic Neurologists and Psychiatrists on campus. I learned how to prepare my diagnostic tools. I was getting to chat with allied health professionals (especially the Physiotherapists) in the Hospital café. Eventually I gained the interest of the Deputy Chief Physio (Ms Mavis Morton). She was interested in learning disorders. The incessant questions and discussions of mine about rehabilitation difficulties and apraxia were sufficient for her to take me more seriously and consider what I’d need to do to get the attention of the Neurologists and Neuro-surgeons who would control access to suitable patients for my research. She suggested I find suitable patients for a single case study, or better two cases for differential diagnosis, and get Dr Dennison or the Head Physiotherapist (Mr Gordon Granger) to get me an invitation through the Chief Neurologist (Professor Guy Gibson) to attend the Neurology Grand Round. The only problem was to get access to the Neurology wards to find suitable patients.

Preparing cases for The ‘Grand Round’

Dr Dennison said he’d think about it. Time went by and he didn’t follow-up on my request for a referral to the Neurology wards or the Grand Round. So I went on sifting through the referrals I could process as part of my Psych assessments.

Could a chronic alcoholic patient be the Candidate?

Aha! - I found a potential patient with apraxia in the General ward G-1. It was a chance encounter with Head Physiotherapist (Mr Gordon Granger) who happened to come down to the G-1 ward to inspect a patient (Mr Rolly Edwards) who was going to be referred to physio because of his severely ataxic gait (typically exaggerated jerky lifting of the legs each step indicating cerebella discoordination of movement). Mr Edwards was laid off from his work as a Gardener because of his chronic alcoholism. His unemployment actually made him drink more, to the extent that he not only had difficulty walking and handling gardening shears properly (ataxia) but eventually he was homeless and found wandering aimlessly in the council gardens. He couldn’t remember who or where he was. The hospital admission in G-1 was for de-tox. But Mr Gordon identified that he had severe enough amnesia to be diagnosed with Wernicke's encephalopathy and severe ataxia consistent with Korsakoff’s syndrome.

As I happened to be in the cubicle next to Mr Edwards when Mr Gordon was discussing this with the Charge Nurse (Ms Anna Pitrella) and the friendly, Neurology Registrar (Dr Harry White).

“We’ve upped the doses of thiamine and glucose for his de-tox, and trying diazepam…” she said from her memory. Dr White replied: “Up them again a quarter, thanks Sister”.

The Nurse took her pen and to my surprise she seemed to write a quick scribble on her leg as she was walking with the two specialists to the next cubicle.

As it happened months ago I’d seen this before when I was observing the Emergency Department intakes to look for any head trauma cases to assess. It turned out that I was fortunate in two discoveries:

Amongst the organised chaos of blood, bandages and trundle beds - the blurr of white uniforms and fast hands emerged an amazing figure: a female Nurse who seemed to be like the “Gun Shearer” in her role of deputy charge Casualty / Intensive care Nurse. Although not tall (maybe 5’4”) and although not the most senior she exuded power and capability in her careful control of rapid actions and clear commands to arriving Ambulance Para-medics. When I accidentally got too close I discovered her roth “MOVE your ASS!” ( I was surprised to hear an American accent) but I was stupefied by her stunning hazel eyes. When the other Nurse brushed me aside I came out of the trance just long enough to step aside and glimpse her Name Tag: “Anna Pitrella” - I was fascinated. She also stood out because of the 4 inch dressing tape she had stuck down the length of her tight jeans of her attractive right thigh. For a moment I thought this is an odd way to dispense bandages second hand off her ‘painted-on’ blue jeans. But then I saw her rapidly grab a pen from her scrubs and writing notes on the tape on her leg. What a great handy idea, this way she had hands free of notepads and clipboards which some of the others attending patients were encumbered with.

I also admired how she handled my next patient: Mr Rolly Edwards. Mr Edwards was a chronic alcoholic Gardener who was carried into casualty with bruises and cuts on his head, knees and hands probably when he fell into traffic while grossly intoxicated. She seemed to know him, not surprisingly as he was a regular at casualty. Ms Pitrella was amazing in her careful way she handled Mr Edwards. He flopped over and spued alcohol smelling vomit over everyone else attending him. But despite her small frame she steadied him enough to get to the far side of the Emergency Department without a messy trail of vomit. It turned out that this was not her real domain, which was the Charge Nurse for the Intensive Care ward. But she was one of the few nurses who volunteered as overload relief for the Casualty ward. So it was I met her again when I visited Intensive care where Mr Edwards had been parked while he was de-toxing and being treated for his not insignificant wounds.

Ataxia vs Apraxia

Mr Edwards would not have been my first choice for my Apraxia case study. His head trauma was not sufficient to cause brain damage. This I had confirmed by the ever vigilant Harry White, whom Dr Dennison had referred me to meet at the ward.

“David reckons you should check out the Korsakoffs as he’s not improving despite the huge doses of thiamin he’s had in the de-tox treatments.” Harry said as we approached the seats adjacent to the Intensive Care ward.

‘Why is he still here?’ I asked just as Nurse Pitrella passed us. She heard me.

“You talking about Mr Edwards?” She asked.

“Yes Anna” Harry smiled- tell our Psych student Dr Pearson here what’s up with Edwards.

‘Sorry Ms Pitrella - I’m just Caspar Pearson - till I finish my PhD.’

“I’m just Anna as I just finished my shift”. She smiled taking off her scrubs as we moved away from the patients to talk. This actually enhanced the change of her demeanour to a more relaxed chattiness than my previous encounters with her terse action orientation on duty.

“Yeah it’s strange Mr Edwards has been here many times and each time he responds well to the thiamin shots, diet and de-tox with much reduction in his ataxia but each time he gets harder to get re-oriented for discharge - like he’s longer term memory is being affected and not just his short-term memory.”

‘Thanks for the Neuro-Psych diagnosis Sister’ I said slightly sarcastically.

“I ain’t your sister buddy!” was the curt reply - then to Harry – “ya- know Harry he’s always getting tested by you and he seems to remember me and you. You’ve seen he can respond to current conversation but doesn’t seem to learn how to do basic or new tasks.”

This was music to my ears - ‘Sorry Anna - Harry what sort of tests were you giving him?’

“Usual numbers forwards and backwards, word associations etc” Harry shrugged his shoulders.

‘So can I borrow him for a few of my own tests please?’

“Yeah Dennison gave you the nod” Harry was now more interested in talking to Anna and checking Edwards’ file.

I smiled at Anna and Harry and quickly tried to introduce myself to Mr Edwards.

I saw him wabbling and waddling away, hands shaking as he tried rolling his own cigarette with paper and filter. But before I could get his attention he’d managed to light up using a match and had taken his first puff.

‘Hey Mr Edwards you can’t smoke here!’ He only stopped when I reached and touched his shoulder.

“Wait a minute” he pulled back “ thiss mine” (slurred his speech indicating some dysarthria);

‘Yes Mr Edwards but not here- I’m Caspar Pearson, I work here so I can take you to a place where you can smoke - OK?’

I got him up to the top floor Psychiatry Department and to my cubicle.

‘Now Mr Edwards we’re going to play a bit of a game and do some tasks. OK?’ He shrugged his shoulders as he seemed to be used to this sort of engagement with professionals.

‘Please show me what’s in your pockets.’ He looked at me strangely - ‘You know you were having a cigarette. When I stopped you and you put away your smokes downstairs - so as I said, up here you can have a smoke. So please show me how skilled you are at rolling your own’.

Again he looked confused. So I patted my pockets and pulled out a pen and paper and motioned to him to check his pockets. Eventually out came the tobacco pouch, match box and papers and filters he had put away when I met him in the ward. As he put them on the table in my office I asked him to tell me what each of these items was called.

“Bacca” for the tobacco pouch - ‘yes thanks that’s right your tobacco in your pouch’ I encouraged;

“Matchies” … “Pappperss” … “filters”, he muttered somewhat confused as to why I’d need to have them named (which I did to dismiss any hint of aphasia, agnosia and memory disorders).

‘Good thanks Mr Edwards, so now show me how to roll your own cigarette to smoke…’

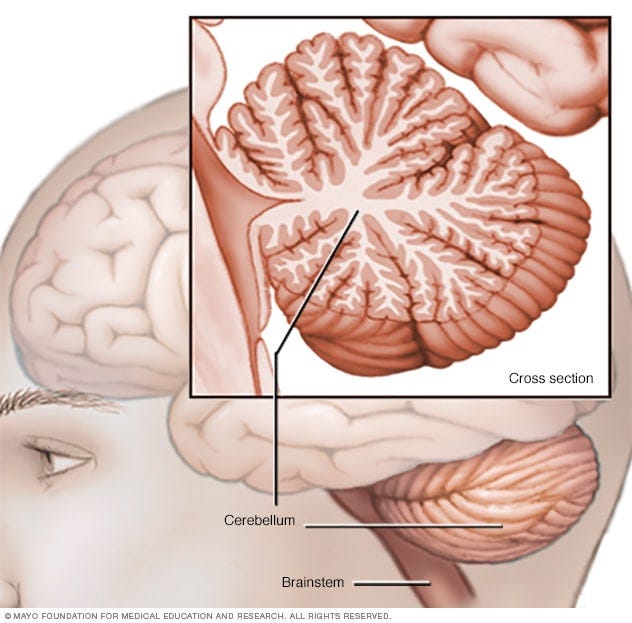

I smiled - and waited as he hesitated shuffling the items around confused and handling them oddly unable to actually put all these together nor actually smoke when told to. I noticed when he was waiting and thinking his shakes were much reduced, and only increased when he intended to move, which is a sign of ataxia[3] due to damage to the back of the brain called the cerebellum, impairing its automated coordination, of voluntary/intentional movement.

Teaching an old dog new tricks?

The hard part of a Neuro-Psychological diagnosis is to apply a true test of whether his learning impairment was due to apraxia and not other impediments like dementia (ataxia was not likely as it is only a movement disorder).

As he was a gardener I tried to get tests which related to his work / comfort zone, so I took him out to the back hospital courtyard lawn:

⁃ ‘Rolly’ (he looked at when hearing his name so he has ability to recognise names) ‘call me Mr Pear -son like the pear fruit but with the son added’ - he could eventually remember my name (which I tested by meeting him without my name tag a few times).

⁃ ‘I brought you a present[4]: Try using this new weeding tool – pull out a weed with it please.’

At first he was curious and immediately grabbed it; but he didn’t know what it was till I demonstrated it on a weed. Eventually he could move his leg to press down to operate this under close supervision, he figured out he could use the main shaft of the tool as a means of balancing, he knew what it was for, but could not reliably improve its use on his own to navigate to the weed, place the tool over the weed, stand steady enough to shift the weight of the guiding foot and move back with the handle as the weed is extracted. The next two days I escorted him from the ward to the back garden and gave him the weeding tool, without instructions to test whether he could use it intuitively. No – each time he fiddled with the tool, tried to stand on it almost falling over, never actually getting to extract a weed.

So it seems I had made some differential diagnosis, by showing it was not anomia, nor aphasia /not amnesia and not ataxia (he could sufficiently coordinate his legs & arms and balance without falling), so maybe apraxia?

The ‘Grand Round’ – a disappointed Psychologist

I was excited to tell Dennison of my progress with Mr Edwards. Eventually I caught him in the lift.

‘Aha – David I think I’ve got it….’

“What? - you still on about the Grand Round?” he brushed me off.

‘Yes of course I think I have a possible case of apraxia.’

“That’s in the form of Rolly Edwards you’ve been parading round the grounds?” he said sarcastically.

‘Yes – I’ve been pararding him round the lawn to test if he can use the new weeding tool I got from the College grounds-man. So I was able to show not only did he not learn to use the tool after 5 attempts over three days, but he didn’t show signs of aphasia, agnosia, amnesia, and anomia. So can I get to show him to the Grand Round please?”

“Alright Pearson – but be ware of what you wish for!” He said with that pejorative tone. “I hope it doesn’t backsplash on me when you flop in front of Guy Gibson!”

Sure enough I was terrified and didn’t do myself justice in front of the great Professor Gibson and his assembled cronies. Just as well I didn’t let MAL know the time or place….

The introduction by Prof Gibson didn’t allow me a good start as we walked past the ward staff to the end room set up as a small seminar venue, where Nurse Pitrella stood holding the hand of Mr Edwards.

“Mr Pearson wants us to believe a Korsakoff is a sufficient example of apraxia, which you all know is a typical Psychologist’s academic exercise anyway! – OK let’s have your differential diagnosis young man….

‘Thank you sir, Ladies and Gentlemen, as you know Neuro-Psychology is relatively new..….’ I had barely begun, when all attending shuddered at the voice from the front.

“Pearson this is not your thesis defence – get on with the history and diagnosis please! Shouted Gibson.

‘Yes, thank you sir….’ I rattled off a brief history, while ruffling through pages of from Mr Edwards’s huge file. Then stood firmly as I could and stared ahead resolutely to proclaim:

‘I tested him with familiar tasks – rolling his own cigarette, which he could do spontaneously, but not by request; and showed him a new task – weed pulling with a special tool he might use as a Gardener, which he could not learn over 5 trials over three days. However, in doing each task I assured that he could recognise the items used, he could name them and he could remember me….’

“Very well then – what are the essential components of the diagnosis of apraxia?”

This was supposed to be a challenge to me which he inevitably expected one of his Registrars to jump in on, as the Grand Round was their Gladiatorial sports arena. But as Apraxia was so unusual a diagnosis, the top team hesitated, just long enough for me to be saved by a slightly familiar face – it was Dr Desmond Brain –a Neuro-surgeon from a rival hospital who was an occasional visitor for the Grand Round.

“I think our budding Neuro-Psychologist has met the criteria for the syndrome, Professor, as he has excluded all the favourites, except dementia, which he didn’t mention, but actually the Wernicke's part of the Korsakoff syndrome could be sufficiently addressed by his test of amnesia.” Several of the assembled smiled sheepishly, except Gordon Granger, who came to the rescue, confidently interjecting from the back:

“Professor you may think a differential diagnosis of apraxia is an academic exercise, but when it comes to the practical science of physiotherapy it is handy to know what we’re up against!”

“Yes well I suppose you need all the help you can get….” Prof Gibson fobbed him off as he moved his attention to the next case in the pile of files and notes before him at his commanding desk.

“Now Nursey” – he gesticulated a resentful finger at Anna Pitrella “clear him off please we have much to do here”.

As Nurse Pitrella turned red with embarrassment and anger, fortunately she was overshadowed by another Nurse who came in smiling prettily and proclaiming:

“Here you are Professor this is Mrs ….” By then I had lost focus on the proceedings and rushed out to be an escort for Ms Pitrella and Mr Edwards, who were already forgotten in the whirlwind of Prof Gibson’s rant about the next patient. I did my best to thank and console her but she was all about the business of the ward before I could build any rapport.

The Moral of the Story: As my Grandmother used to say “Nothing is as bad as it seems”

Dejected I slowly recounted the complex and frustrating events of the last week culminating in my apparent whitewash, to MAL and some of my Psych students, when I received a surprise visitor: Dr Harry White, who charged in and gushed approval, as he had been a silent witness to my moment of professional grief:

“Beudy mate- you survived and not a bad case either! – Oh sorry was I interrupting?”

‘Glad you could find the remnants of me – lucky to have carried myself here after that debacle!’ I almost sobbed.

“Nonsense Caspar you held your own against the old bastard, and you survived the cross-fire of the usual brawl between Granger and Gibson” he re-assured me. “I looked for you down the pub – which is where you should be celebrating!”

‘Thanks mate – I actually should be holding a Tute about now… anyone object adjourning to the pub?’

“No – go for it …”

There were other assorted eager replies as the students demonstrated that they would rather the opportunity to go out and celebrate with me, than be taught drearily by me.

After the obligatory few drinks and my long-winded account of the events of the day, punctuated by many a cheer, I was walking back to college when it hit me:

A syndrome is really just an academic stereotype, a convenient cluster of behaviours with assumptions and potential biases. The differential diagnosis has to be able to overcome the simplistic assumptions of the label given the patient and their behaviour. A critical thinking professional may start with the hypothesised syndrome but has to bring sufficient practical evidence to be able to demonstrate a differential diagnosis to sceptical peers. Even then the true test of the accuracy of the diagnosis is whether it aids in the treatment of the patient.

Unfortunately for Mr Edwards, the accuracy of my diagnosis meant he was eventually dropped down the list of the Physiotherapy roster, in favour of patients who could learn to improve.

[1] I write these notes so that others may learn from my experience and reflect on my lessons learned from these cases from a burgeoning practice of psychology. I share these events and analyses of the people and psychology – recounted as best I can, given the efflux of time and the constraints of confidentiality. So the names and places which appear herein have been changed to cover for the concerns of clients and institutions.

NOTE: All images are from Substak.com photo gallery.

[2] Caspar’s cases #4: The “Andrea the Autodidact”

[3] More on this at: https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/ataxia/symptoms-causes/syc-20355652

[4] I couldn’t actually give it to him to practice with, or risk him flogging it off for cash, as I’d borrowed it from the College grounds-man Angus Arthur – but he assured me I could use it till next week.